Five lessons Britain can learn from the successes of the London 2012 Olympics

As Paris prepares to open its Games, what are the lessons of the capital's Host City legacy for the UK and its new government?

I won’t pretend the article below isn’t designed, at least in part, to persuade you to buy a copy of my book Olympic Park: When Britain Built Something Big, which tells the story of how London became the host city for the 2012 Olympic & Paralympic Games, how what is now called the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park came to be built, and how, post-Games, that Park has evolved into a whole new London neighbourhood.

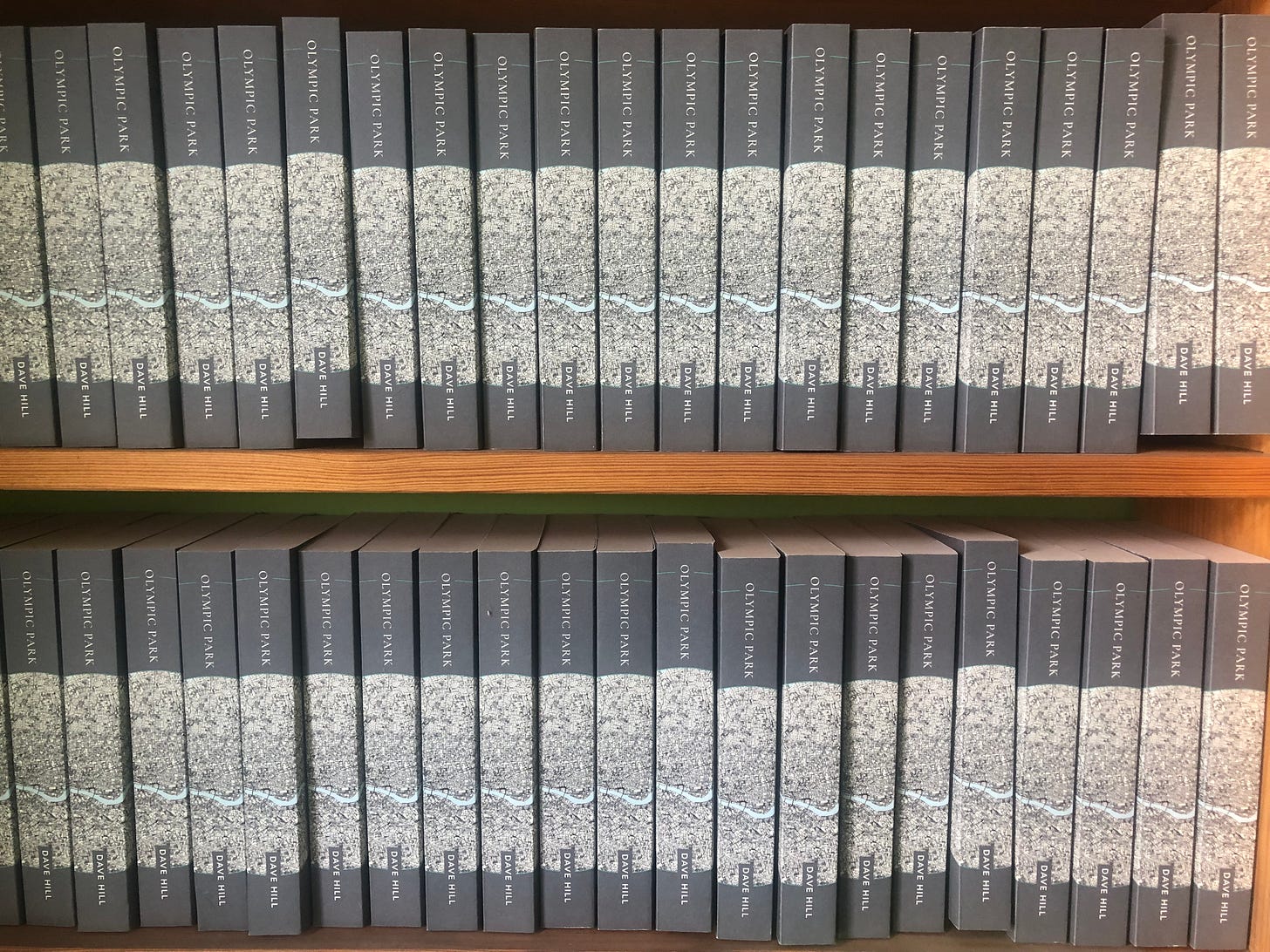

I sweated blood over the book, which was published two years ago, interviewing over 50 people who were involved in the Games story, getting it professionally designed and edited, and producing it at my own expense after no agent or publisher picked up the idea. Well over 800 copies have been purchased, the great majority directly from me or from my local independent bookshop, Pages of Hackney. I would love to get that number up to 1,000.

Still with me? If so, read on below the photo. Thanks, Dave.

On 5 July 2005, just over 19 years ago, London was named host city for the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. Right up until the final minutes, Paris, which will very soon host the 2024 event, was the favourite. London’s chances had improved as the bidding process progressed, but few expected the capital to overcome the UK’s reputation for making a big mess of completing major infrastructure projects - and redeveloping the Lower Lea Valley in the east of capital next to Stratford in order to stage the largest sporting festival in the world definitely qualified as one of those.

How did London prevail? There were loads of reasons, not least the vision, skill and persistence of people whose efforts went largely unnoticed. Reflecting on those efforts and the successes of the Games themselves and their still-unfolding legacy, I’ve come up with a list of five lessons from the London 2012 experience that the UK’s new national government might learn from as it sets about rebuilding a tired, damaged and cynical country. Some of the principles concerned show signs of already being followed. Fingers crossed that that continues.

1: National, regional and local government working together

There was little love lost between, on the one hand, some very senior members of the Labour national government of Tony Blair and, on the other, Ken Livingstone, who had become the very first Mayor of London running as an Independent after failing to be selected as the Labour candidate. Also, it was notoriously difficult to get London’s local authorities to co-operate with each other, something badly needed in the early stages.

Yet through the application of political will on all sides, huge financial, planning policy and personal relationship barriers were overcome in order to put a convincing Host City bid together, build the Park within budget and in good time and ensure that the enormous transport, security and other preparations were all in place.

It was a rare triumph of local, regional and national government co-operation that went on to survive Conservative politicians taking over from Labour at national and City Hall levels, in 2010 and 2008 respectively - a truly cross-party endeavour.

2: Delegation and trust

The UK Treasury has a considerable reputation for hoarding power unto itself, typifying UK government’s high degree of centralisation. Yet where the Olympics were concerned the government’s financial chiefs showed a rare willingness to delegate the completion of a key national project to capable people - perhaps most notably David Higgins, who led the Olympic Delivery Authority - and allow them to control the spending of the budget required.

There was rigorous external scrutiny of how money was spent and proper criteria had to be met when pre-agreed safety-net contingency finds were asked for. But there was next to no disruptive political interference, no stop-go funding streams, no top-down micro-management. People who knew what they were doing were allowed to get on with their jobs - and they did them well.

3: Backing big city public transport

The expectation of the Olympics top brass was that everyone would move around by motor car. The very earliest designs for the Park itself featured loads of new roads. During the run-up to 2012, the media was full of dire predictions of “transport chaos”. And yet, when it came to the crunch, London’s Underground, Overground and other rail services, strongly reinforced with extra capacity, rose to the occasion.

Peter Hendy, the Games-time TfL commissioner and now chair of Network Rail and a newly-appointed transport minister in the House of Lords, has described London 2012 as “the first public transport Games”. He was right and they were a triumph.

4: Loving London

It seems extraordinary that so soon after the glories of London 2012, with the Park legacy he did a lot to secure and enhance still taking shape, Games-time London Mayor Boris Johnson’s national government went out of its way to slight and discriminate against the UK capital, not least by poking its nose into City Hall business at every opportunity.

An entire school of anti-London sentiment, egged on by parasitic right wing populists like Nigel Farage, now derides the very characteristics that helped London become the 2012 Host City in the first place and then to make such a huge success of the Games themselves. Things like the city’s global reach, its polyglottal, multi-ethnic population, its boast of containing the world in one city.

The new national government has gone out of its way to say that, as far as it is concerned, those London-bashing days are gone. The national interest requires nothing less.

5: Building for the long term

The London 2012 bid was founded on a pledge that the Park would not only remain in use after Games were over, but developed into a lasting new part of the city. That promise has been kept.

All the permanent sporting venues have, one way or another, been adapted for continuing use, including by the general public. The East Bank project is close to completion, with its cluster of educational and cultural institutions bringing new kinds of life and energy to the Park. New housing continues to come out of the ground.

We can debate the pros and cons of this or that aspect of the Park legacy and the decisions that informed them, but no one can seriously dispute one thing - that where other Olympic parks have been left dormant or to decay, London’s has grown and grown. Its Games legacy stands head and shoulders above any other…and it was always meant to be that way.

Buy Olympic Park: When Britain Built Something Big either directly from me or from my local independent bookshop, Pages of Hackney. Please note that the cost of posting books overseas will be higher than listed on the OnLondon website.

Thanks again!