Katie Lam should learn London’s language

Recent comments about the capital's school children's English skills suggest the Tory MP from Kent must try harder

Half the stuff I publish here is free. Paying subscribers get the other half and offers of free tickets to top London events. For £5 a month or £50 a year, they also help support my all-free multi-contributor media empire OnLondon.co.uk, where this article originally appeared.

Tory MP Katie Lam, ascendant in her sunken party, has been in a spot of bother for telling a newspaper that “a large number of people” who live in Britain entirely legally “need to go home”, because she happens to believe they should not have been allowed to live in Britain in the first place. Realisation of this deportation vision would, she continued, leave “a mostly but not entirely culturally coherent group of people”.

Less attention has been given to a remark she had previously made at a Conservative conference fringe meeting about immigration:

“There are schools now in London boroughs where more than three-quarters of children don’t speak English to a serviceable school standard.”

It was quite a claim. Which schools? Which boroughs? How have London’s schools been as successful as they are at equipping children with good qualifications if an inability to speak “serviceable” English has been as commonplace among them as Lam seemed to suggest?

I made some inquiries. The event was organised by the Centre for Policy Studies (CPS), a well-known right-wing think tank. Could it provide the source for Lam’s assertion? I asked Lam’s office the same thing.

Both replied with a link to a 13 year-old article in what was then the Evening Standard. Drawing on a Greater London Authority report, this said that more than 70 per cent of primary school pupils in two of London’s 32 boroughs, Newham and Tower Hamlets did not speak English in their homes. It had nothing to say about London primary school pupils’ proficiency at speaking English, which is a different matter and was the subject of Lam’s remark.

The CPS also suggested I read an article by Neil O’Brien MP, another pugnacious Tory protagonist in the current hostilities about what Britishness is or ought to be. And Lam’s office also pointed me to an item on the right-wing TV channel GB News, which mocked a London council’s video made to assist people with poor English skills navigate its housing allocations scheme – housing which a perky presenter described with relish as “subsidised” in a very expensive area. That wasn’t about London school children’s proficiency in spoken English, either.

I contacted Lam’s office again. Surely they could do better than that. And, fair play, they tried.

A second response informed me that it is an “uncontroversial fact” that “a number” of schools in London “now host a large majority of pupils who do not speak English as a first language”. As with Lam’s assertion, it didn’t say what size that number was. However, the reply graciously acknowledged that, as I had pointed out, “EAL [English as an additional language] status alone does not necessarily reflect degrees of proficiency”. But it went on to refer to the Department for Education’s most recent report on the English-speaking prowess of EAL pupils in English schools. This, the reply said, showed that “English fluency” was put at 12 per cent among Reception class EAL students (four and five year-olds) rising to 22 per cent among those in Year 2 (six and year year-olds).

Earlier in the reply, an east London primary school had been described as “the first school in England where no pupils speak English as a first language”. The school in question, I was told, had been the “subject of reports” earlier this year. There was, I was assured, “no strong reason to believe” that a school like the one named “would differ significantly from these national norms”. As such, the reply concluded, “it is extremely likely [their emphasis] that more than three-quarters of pupils” at a school “like” the one mentioned “do not speak English to an EAL level of fluent”.

There’s quite a lot to sort through here.

The essence of Lam’s assertion, as expressed in her CPS event remark and the replies from her office, is that in an unspecified number of London schools of unspecified types – Lam and her office didn’t say if they were talking about primary schools, secondary schools or both – there are large majorities of pupils who do not speak English to a level Lam regards as “serviceable”, and that is because English is not their first language. Yes, EAL pupils can be or become proficient at speaking English, but the rates of such attainment were low.

Behind all this, of course, lie contentions about immigration, integration, and a “coherent culture” that Lam would soon after articulate in her newspaper interview.

Let’s look at that most recent DfE report about the spoken English proficiency of school students for whom English is an “additional language” – the one to which Lam’s office directed me. Assuming I have the right one, it was published in 2020 and refers to the situation in 2018.

It says that 19 per cent of all school pupils in England at that time had English as an additional language – 1.6 million out of 8.1 million. It adds that 36 per cent of those EAL pupils were judged “fluent” in English and a further 25 per cent as “competent”.

Lam’s office referred to “fluency” but not to competence. Lam herself used that word “serviceable”. Things described as serviceable are considered “good enough to be used and to perform its function“. A child judged “competent” at speaking English is quite obviously able to do so to “a serviceable school standard”. So that’s 61 per cent (36 plus 25) for all ages across England as a whole out of the 19 per cent who have EAL whose English is fluent or competent and therefore “serviceable”.

If, for the sake of discussion, we assume that the non-EAL 81 per cent are fluent or competent in English – something the report itself says we cannot – that makes an average of 92.5 per cent of all pupils, covering the entire age range, who are fluent or competent in English and just 7.5 per cent who aren’t. That’s a long way short of the “over three quarters” Lam claimed can be found in “some” schools in London.

What about London in particular, as distinct from England altogether? London has by far the largest number of EAL pupils of any region: 560,206 in 2018, according to the DfE report, and 578,833 in 2023, according to an Oxford University study funded by the Bell Foundation, a language education charity, published earlier this year. That number represents 44.3 per cent of all London school kids (1.31 million in total). How many of them are fluent or competent English speakers?

The DfE report notes that, among EAL pupils of all age across England as a whole, “English proficiency levels are highest in the South East (66%) and London (65%)”. So although Lam picked out London for special mention at the CPS event, as a region it has one of lowest levels of not “serviceable” proficiency at speaking English among EAL pupils – about one third of them, accounting for about 15 per cent of all London school kids – again, a lot less than the three-quarters of them, the at least 75 per cent, Lam said “some” London schools contain.

The DfE report also provides a breakdown of fluency and competence levels by local authority area as of 2018, including all 32 London boroughs and the City of London (pages 23-26). The highest combined levels of fluency and competence among EAL pupils in London, at 77 per cent, were found in Camden and Bromley. The lowest were in Lambeth (54 per cent) and Barking & Dagenham (56 per cent). So even at the bottom of the London borough league table, more half of EAL pupils across the full age range spoke English to a standard that is “serviceable”.

Does this evidence prove that there are absolutely no schools at all in London, of any kind, where “more than three-quarters of children don’t speak English to a serviceable school standard”. Of itself, no. But it does rather suggest that if such schools exist at all, there are vanishingly few of them.

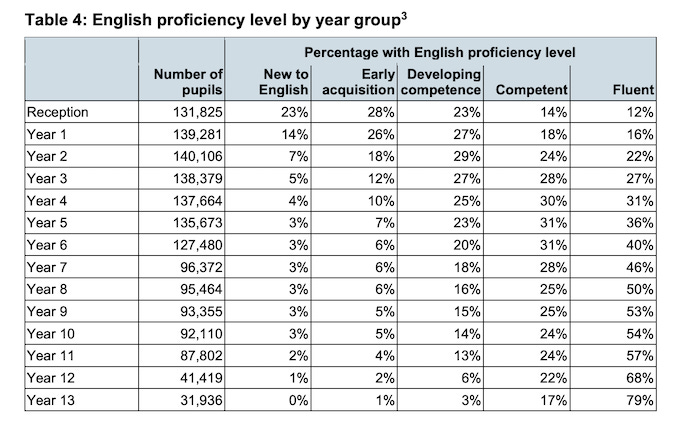

The DfE report contains a national (not London) breakdown of EAL pupils’ proficiency by year group (table 4, page 8). It shows that by Year 11, (GCSE time), 57 per cent had been fluent and 24 per cent, competent, making at least 81 per cent speaking English to a “serviceable” standard, with a further 13 per cent assessed as “developing competence”. Of those who continue to Year 13 (A-levels), 79 per cent of EAL pupils were fluent in English and another 17 per cent were rated competent – highly “serviceable” pretty much wall-to-wall.

However, London’s schools do, on average, contain considerably higher percentages of EAL pupils than other regions of England (more than double its average figure, the Oxford study says). Could there be “some” schools where the percentage of EAL pupils is so high and their fluency or competence in spoken English so low that they do indeed contain “more than three-quarters of children [who] don’t speak English to a serviceable school standard.”

Here we return to Lam’s office drawing my attention to “the first school in England where no pupils speak English as a first language” – a primary school in London which had been “the subject of reports” earlier this year. The reports in question turn out to have been by right-wing media organisations, though one of them was good enough to recognise how popular it seems to be with parents and children. The school in question was also subject to a different sort of report earlier this year – an Ofsted, which praised its “calm and respectful environment” and provision of experiences that help to “build leadership, teamwork and communication skills”.

But what about the spoken English capabilities of its pupils? The Ofsted report makes no mention of that. But Lam’s office claimed it is “extremely likely” that more than three quarters of pupils at schools “like” the one concerned “do not speak English to an EAL level of ‘fluent’.” To buttress that point, it said there is “no strong reason to believe” that the school “would differ significantly” from the “national norms” for EAL pupils it had drawn my attention to in the DfE report.

Well, Lam didn’t say “fluent”. She said “serviceable”. And her office only mentioned the “national norms” for Reception and Year 2 pupils. Primary schools go up to Year 6. So let’s accept that every child in the primary school in question is an EAL child, and see how proficient we might expect them to be at spoken English if the DfE report data from 2018 in Table 4 is taken as a predictor, as Lam’s office suggests.

I’m not the best at maths. But by my ready-reckoning, this shows that the average fluency level for EAL pupils in Years 1 to 6 in England is 26 per cent, or just over a quarter. So even by that strictest definition of “serviceable”, slightly fewer than three-quarters – not “more than” – would fall short. And if we include “competent” within “serviceable”, as we surely should, that average rises to 51 per cent.

So even if every child in a primary school is an AEL pupil, fewer than half - not more than three-quarters - will lack “serviceable” spoken English, if the DfE report figures are any guide. Moreover, by the time EAL pupils England-wide have reached Year 6, those fluent and those competent add up to 71 per cent nationally. Stick on a London top-up, and any school in the capital with no non-EAL pupils at all would have, in its highest age group, around three-quarters of pupils whose English was “serviceable” as opposed to not, and on course to grow.

What Lam did at the CPS event (pictured) and what her office has tried to justify, was spin out a line based on cherry-picked statistics and partisan media coverage in the cause of making a larger argument about the virtues of requiring everyone living in Britain to conform to a narrow set of norms she deems acceptable and essential – an argument whose dark, authoritarian, Trumpian logic she has gone on to make explicit.

Apart from anything else, it revealed an alarming ignorance about the strengths and human character of the UK’s capital city, her country’s global beacon and economic powerhouse. It is she who is culturally incoherent. She needs to learn London’s language. To put it kindly, she really must try harder.

This is such a useful article. It is so important that articles like this which are fact-based, calm and analytical, are published and widely disseminated. The space for misunderstanding and getting things deliberately out of context has never been greater. This is very much appreciated.