London history: Some stories and locations, lost and found

A small selection from the rich archive of articles written by Vic Keegan for my multi-contributor journalism website OnLondon.co.uk

As usual, I’m spending part of August ploughing through backlogs of admin and correspondence, hoping people will forgive my neglect, and wondering why I’m not getting out more. I’m also writing a bit less, there being only 24 hours in each day.

These things explain why this post is a fairly random compilation, a quick mini-greatest hits, of some of the very many articles written over the years for OnLondon.co.uk, my multi-contributor journalism website, by Vic Keegan, who I’ve known since my days as a contributor to the Guardian, where he was a senior writer.

Vic has a deep interest in London’s history. He wrote a long series of articles for On London called Lost London, which concentrated on locations associated with significant buildings, people and events, in many cases largely forgotten about.

He also wrote two “supported content” series for the website that were funded by the business improvement districts, Central District Alliance and EC BID. As well as generating excellent articles, these deals topped up the revenue from individual website supporters - who now including paid subscribers to this personal Substack - which accounts for most of On London’s income.

I might not be getting out much at the moment, but that doesn’t mean I can’t help you to. That is the spirit in which I’ve picked half a dozen items from Vic’s extensive On London back catalogue to bring to your attention. All concern London places that are eminently visitable and, of course, just really interesting to read about. Below are my six Vic Keegan picks, complete with their main images and opening paragraphs.

Lost London 212: Finding Lundenwic.

How many people gripped by a performance at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden realise they are sitting above the remains of a once thriving Saxon settlement? The discovery of Saxon London – it stretched along the Thames from Trafalgar Square to the start of Fleet Street – is the capital’s biggest postwar archaeological discovery. Continues HERE.

Lost London 221: Jack Sheppard’s Criminal Vapour Trail

If you are going to write about London’s most charismatic criminal of the early 18th century, where better to start than the Rummer Tavern and brothel shown in the William Hogarth engraving above, just off Trafalgar Square. It was there, in 1722, that Jack Sheppard committed his first offence – stealing a couple of silver spoons a short distance from where he is buried at the nearby church of St Martin-in-the-Fields. Continues HERE.

Lost London 244: Dick Whittington’s Very Long Lavatory

On or around 1 May 1421 a public toilet built over a dock on the Thames by the mouth of the River Walbrook opened its doors. Called the Longhouse, it had an amazing 128 seats – 64 for men and 64 for women, something you might only see at big pop concerts these days. Its contents were discharged through a gully underneath and carried downstream at high tide. Homes were built above it to utilise the space created. Continues HERE.

Two Ancient Churches of Cornhill

Cornhill is the centre of gravity of London’s historic financial district and one of the three ancient hills of London, the others being Ludgate Hill and Tower Hill. As its name suggests, corn was once traded there. The three hills are not as famous as the Seven Hills of Rome, and it requires an act of faith to believe they even exist because, thanks to London’s constant growth, they are no longer in plain sight. Continues HERE.

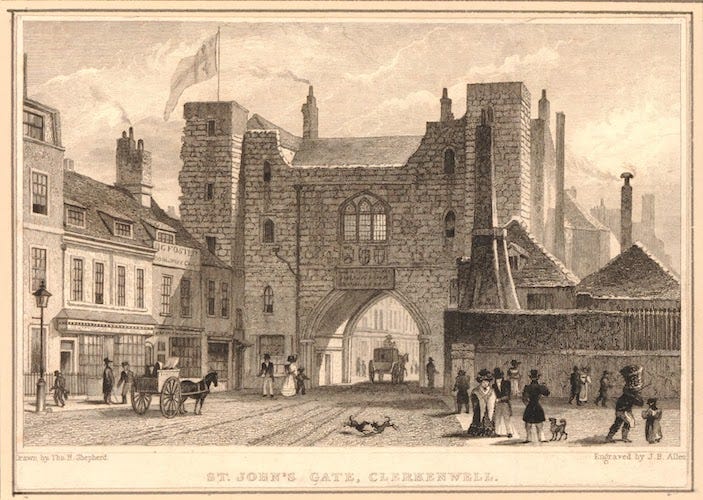

Edward Cave, the magazine trailblazer of Clerkenwell

In January 1731 the seeds of a breakthrough in journalism were sown in the unlikely setting of the gatehouse of an old priory in Clerkenwell. It was from there, at St John’s Gate, that Edward Cave launched a monthly publication called The Gentleman’s Magazine, which has a good claim to being the first of its kind in the English-speaking world. Continues HERE.

Sir Thomas Gresham, the City’s first “true wizard” of global finance

In prime position in the charismatic church of St Helen’s Bishopsgate lie the remains of Sir Thomas Gresham, one of the most influential and enigmatic figures the City of London has ever produced. Gresham, who lived from roughly 1519 until 1579, was hugely rich, with a palatial home in Bishopsgate where Tower 42 is today, yet he died heavily in debt. Continues HERE.